WEEK SIX

- Angie Moyler

- Jul 20, 2022

- 10 min read

Updated: Oct 8, 2022

Interdisciplinary insights, new approaches and creative partnerships.

Power with, instead of power over.

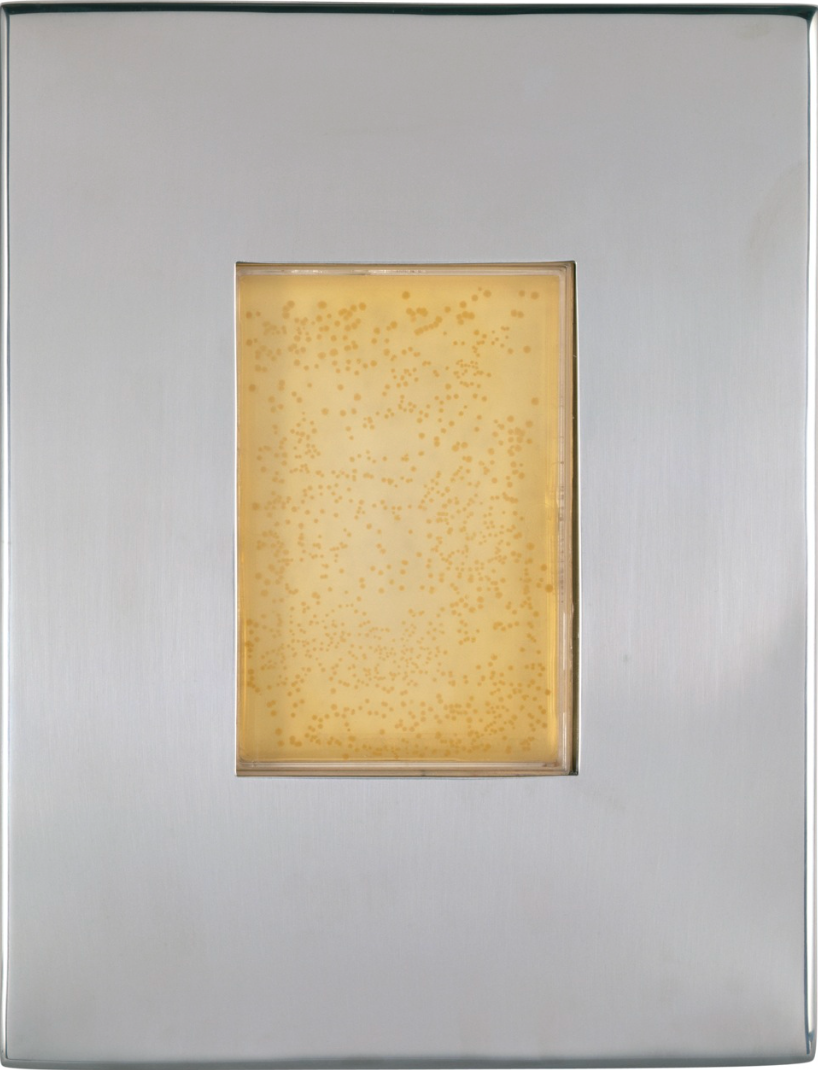

IMAGE 1

This article is fascinating. It looks at four interdisciplinary collaborations. I have highlighted interesting quotes from each;

The artist and the geneticist.

Just before 9/11, Marc Quinn did a portrait of Sir John Sulston, one of the genetic scientists who decoded the human genome. "At the moment this divisive attack happened, John's work and this portrait were suggesting that we are all connected – in fact that everything living is connected to everything else," Quinn says.

"Some say it's an abstract portrait, but I say it's the most realistic portrait in the National Portrait Gallery," says Quinn. "It carries the instructions that led to John and shows his ancestry back to the beginning of the universe."

"Well, yes," says Sulston, "but DNA gives the instructions for making a baby, not an adult. There's a lot more to me than DNA."

Did the collaboration change each man's attitudes towards the other's discipline?

"I still think science is looking for answers and art is looking for questions," says Quinn.

"Science simply means finding out about stuff, but in that process science is the greatest driver of culture," says Sulston. "When you do something like decode the human genome, it changes your whole perspective. In terms of genetic manipulation we're not just looking for answers but modifying what's there."

IMAGE 2

The poet and the speech scientist.

"I once overheard someone say, 'Its mother was a crab,'" says Valerie Hazan, professor of speech sciences at University College London. "Can you think of a situation in which that would be used? I often ask my students this."

I love this! One of the practices I encourage in my students is to 'ear-wig'. Socially frowned on but oh so interesting! Even just catching interesting words or phrases to include in content, to gan an insight in to the lives of others, or like this - to spark an idea.

Hazan's point is that hearers often work imaginatively to supply a context to a discombobulating utterance, to annex incomprehensible or uncanny speech into the more soothing realm of the understood. But there's another point, too: "Certain utterances stick in your mind: a contorted use of language not planned in any way is often most memorable."

For her latest project, Greenlaw spent two years eavesdropping on passengers at railway stations.

Is there any parallel between the two women's disciplines? Hazan says: "As a scientist you have to be creative to really think what is the question. I didn't think a poet had to be methodical."

Greenlaw says: "Poets are often thought of as vague and wishy-washy, but, like scientists, they can't be. A poem can be about vagueness, but it has to be in precise relationship to vagueness if it's any good. I'm ridiculously analytical. Poetry, though, is an unsettlement – unlike you, Valerie, I'm not drawing connections."

"But we're both manipulating reality to understand it," says Hazan. "What makes a good scientist is someone who can see beyond the obvious."

The photographer and the physiologist.

When Mary Morrell and Catherine Yass collaborated on a project called Waking Dream, each hoped to unravel what, if anything, essentially happens in the transition from sleep to wakefulness.

Both women say working on Waking Dream broadened their horizons. "Catherine challenged my preconditioned ideas," says Morrell. After the collaboration, she took a photography course. Some photographs from mountaineering jaunts hang on the walls of her office.

"I was inspired by your attitude," says Yass. "I came with a tentative idea and you would say, 'This is how you can do it.'" Could Yass imagine having been a scientist? "I used to think about being a brain surgeon, but I wouldn't trust myself in a million years. In terms of science, I've always been daunted by the amount of knowledge a scientist needs, but I love the idea that there's a lot of knowledge and someone like Mary has it."

The theatre director and the neuroscientist.

"If you hear a recording of someone whispering in your ear," says theatre director David Rosenberg, "you can convince yourself you felt their breath."

"Expectation is everything," agrees Professor David McAlpine, director of London University's Ear Institute. "Your brain fills in so much it's not funny. You've got a very narrow bandwidth by the time you get to your ears and your eyes. The rest is artificial, filled in by that expectations machine – your brain."

For his latest theatre piece, Electric Hotel, Rosenberg wanted to play with some of these auditory ideas, to tease his audience with sound illusions. So he approached neuroscientist McAlpine, whose research work into brain mechanisms for spatial hearing and detecting sounds in noisy environments proved key to the effects Rosenberg wanted to achieve. "We were trying to create a very intimate experience for an audience in a show which they see from a distance and also through glass," says Rosenberg.

McAlpine recalls the most sophisticated binaural illusion he ever heard. "I was at Dolby's headquarters in San Francisco. They made me put on headphones, close my eyes and then you hear you're in an aeroplane and you crash into the ocean. I really felt a sense of the whoosh of water and the sense of going up on to a sandy beach. Those sensations were my brain filling in the experience from what it heard."

I never cease to be amazed by human creativity, especially when enhanced with a collaborative instinct.

CHALLENGE

What are the advantages of interdisciplinary provocation and how could you utilise this approach in your practice?

Put theory into practice and spend an hour brainstorming ideas based on the following challenge and who you would choose to work with.

Identify a discipline and specialist who could help you to reflect from a dynamically opposing position on a specific problem.

Pick one of the issues below and discuss with your chosen individual how you may solve the challenge. This should ideally be recorded as an audio podcast. Our interest in this also relates to the way in which different disciplines discuss an issue and their manner and approach in communicating differently, as well as how you would capture this.

As a guide, please evolve your own strategy for bridging the questions. Equally, you may wish to also consider the core issues: how would your specialism solve this and how different is this to the expected design thinker?

Do not forget to consider the communication style you would use to encourage interdisciplinary dialogue.

Finally, how do you summarise these findings in a way that is acceptable to both collaborators?

I understand the question of the advantages of interdisciplinary provocation and how could you utilise this approach in your practice from the perspective and core principle of always allowing the idea to lead and the richness found in including others. Not to be stunted and compromised by a limited skills set or lack of knowledge. If you don't have the skills to realise the idea either learn them or buy in someone else who does.

In my experience successful design comes from effective collaboration which demands an inclusive, open, curious mind set. Not restricting the idea to your own skills. It comes from knowing that a different perspective enriches and adds value to any idea. Creativity in isolation can be very shallow and self serving. At times an effective personal mindfulness activity, but the transformation and ability to pay your rent is found in intentional collaboration.

As a freelance graphic designer, the art and need for interdisciplinary collaboration is essential. Any success in the competitive world of self employment demands an innate curiosity, the ability to take a risk, a teachable demeanour, a level of confidence and a genuine interest in the lives and thinking processes of others.

IMAGE 3

To connect interdisciplinary collaboration to the everyday life of a freelance graphic designer a reflection on my work with setting up The Oxford Charcoal Company is an interesting angle.

I will use this to answer the questions in place of a podcast or interview.

This business venture involved setting up the first eco friendly charcoal production company in the UK via a burner imported from the Ukraine. The first of its kind in the UK.

Initiating this venture was an already successful businessman. This brought the business acumen and the investment backing. To that add the most knowledgable mind on British woodlands and all things around the science of charcoal. Two very different disciplines each with their own specialisms and ways of thinking. The potential seemed a safe bet - if the common ground could be found.

Add a graphic designer in to the mix and you have three totally different ways of thinking and looking at the challenge. But - the common ground is the design thinking or integrated thinking process. To be effective this has to start with human need, people and culture. Innovation comes from empathy and understanding human need. This then translates to participation with others through connecting on an emotional human level. When these elements exist between different practices then the common ground is found and the creativity from each discipline becomes cohesive and therefore productive. The same foundational questions asked throughout the process - why? how? what? etc undergird the whole process.

When I was first approached to help set up this new business as a brand developer, designer and content creator I had little idea of the whole other universe I was jumping in to. But - I knew I was on the same page as Charcoal Matt as we shared the same design thinking approach.

I knew nothing about charcoal. I thought you dug it up. We all do ... right? But I knew Matt and I knew we shared some core values. Therefore, our two different professional practices would be able to find a common ground.

That was how I started. These were the three 'dynamically opposing positions on a specific problem.'

The reason this story works with this topic is that it was and still is a success. It worked because the three main players involved at the beginning - myself and Charcoal Matt and the business partner, had the same attitude to each others discipline. As outlined in the ethos section of this module and in this blog, successful graphic design is so much about the attitude and approach of all those involved in any collaboration as it is - in my case - about colours and fonts and logos and software. Charcoal Matt and myself read from the same page. Therefore we both learned - an awful lot - and took risks to deliver a successful outcome.

IMAGE 4

Once the brand was up and running and selling charcoal and almost as many

t-shirts and hoodies as bags of charcoal, we were given the challenge to get the product in to Waitrose within a year of production.

After we got up off the floor we heard ourselves saying 'Yes, of course. No problem.'

And then went off to twitch in a dark corner.

But, it worked - and we did ... get the charcoal in to Waitrose - not twitch in a dark corner ... actually that too!

IMAGE 5 The first shipment off to Waitrose.

The resulting transaction involved stepping up to another interdisciplinary collaboration.

A graphic designer negotiating with buyers from a giant retail company for the first time.

But, I had a huge level of confidence in the knowledge and backing of rest of the team and have always been happy to take a risk.

A successful interdisciplinary collaboration. To summarise - the business is a success because the initial business was formed with the overriding attitude to connect with human need. Therefore the brand image and ethos is able to be 'heard' by the intended community.

Successful Interdisciplinary Collaboration involves an appreciation of Anthropology.

In order to further develop the initiative SPARK I have associated with this project the practice of Design Anthropology will be an interesting and fruitful avenue to explore. Quotes taken from this piece of research fit well with my thinking and with the subjects of this module;

Design anthropology is a form of applied anthropology that makes use of ethnographic methods to develop new products, services, practices, and forms of sociality. It is reflective with its foundation squarely rooted in the anthropology theory and practice of cultural anthropology, yet also deliberately and openly prescriptive with its future-making design orientation.

... design anthropology should no longer be thought of as research in service of designed artifacts, nor as an anthropological study of design. Instead, design anthropology should be thought of as a philosophy and practice for creating a true partnership among stakeholders with the goal of designing for good, by being aware of the past, but seeking to positively transform the future.

Design anthropology should also not be thought of as design thinking. While design thinking is a human centred practice similar to design anthropology, they are distinct,

During my work in writing graphic design projects I have regularly read work by the Design Anthropologist Dori Tunstall - Associate Professor of Design Anthropology, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne.

In her book Design Thinking and Other Noble Persuits, Debbie Millman transcribes a conversation with Dori Tunstall. Quotes taken from their conversation connect back in to my ethos, research and design thinking around the initiative of SPARK;

Does the process of design define what it means to be human?

Yes. Design translates values in to tangible experiences.

As Debbie Millman says -

'if I wasn't working at a job I loved, or had the flexibility of a sabbatical, I would pack up my bags, move to Australia, and study design anthropology with Dori Tunstall'

(Millman, D. 2013)

As this blog has highlighted, in order to design effectively for the current local and evolving global community there is an increasing need to understand human behaviour.

Anthropology is a fascinating social science specialism to enhance the role of any graphic designer. I would even say it is a crucial part of a graphic designers educational foundation in order to add critical depth to design thinking.

An appreciation of design anthropology enables a graphic designer to add a deeper level of context to their ideas in order to target their questioning and research resolving a design challenge with greater insight, thus providing a more accurate response which respects the community and therefore includes, connects and allows collaboration to happen.

‘Dori Tunstell suggests a shift in design education to focus on how students and staff exist ontologically, or ‘be,’ in the world rather than solely how they see the world.’

Webinar take aways;

During this weeks webinar I was very much taken with the notion of non-hierarchical collaboration. As a rule I double check why an idea, word, phrase or comment stands out from others. Hierarchical structures are so prevalent in our society and how we function. This is where position is used to abuse power. I do not think power in itself is negative - it's how it is used. An hierarchical structure in itself is not destructive, but perhaps the individuals attitude to their position and to self can be.

For me power with, instead of power over releases people to be who they are and allows innovation and transformation to flourish. This environment then fosters a collaborative mind set, extending creative possibilities.

Interdisciplinary practice by definition negates the abuse of hierarchy - because there is none!

Rhizome - maybe this could be a great name for my design curriculum? :)

CHALLENGE - How to introduce design anthropology in a SPARK project or any other original idea.

Comments